Business Leadership Writer Talks Work Culture Trends, Past and Present

From blurred lines between professional and personal life to screen apnea to Gen Z “shaking the table,” author Amy Federman shares her insights and lessons learned.

This is part two of my interview with Amy Federman. For Amy’s full bio and more, check out part one: South Philly Author, Editor and Ghostwriter Reveals Why She's Ready To Be Unmasked. “Amy Federman opens up on Tourette's, being a late bloomer, and facing fear head on. She says midlife is a time to pull bullshit out at the root.”

For almost a decade,

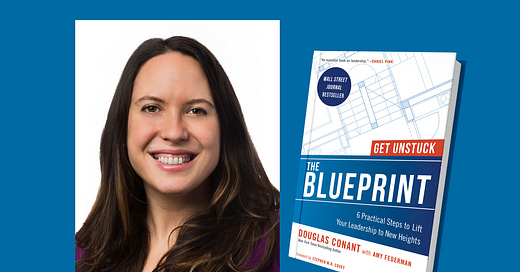

has been managing content for ConantLeadership. She co-authored a book with the founder, Doug Conant: The Blueprint: 6 Practical Steps to Lift Your Leadership to New Heights is a WSJ best-seller. As the current Editor in Chief & Director of Content, Amy regularly writes newsletters about workplace trends and ideas.On

— “a newsletter in the spirit of a party abuzz with good conversation” — Amy writes fabulous and thought-provoking essays you’ll want to reread. Amy lives in South Philly with her husband. You can find her at @amyfedermanauthor on Insta and Threads, at @AmyFeds on X (Twitter) and as Amy Federman on LinkedIn.This interview took place before the 10/7 terrorist attack in Israel. In light of the tragedy, Amy is taking a mental health break from social media.

Your ConantLeadership newsletter covers trends in work culture. Can you share a recent one that you think is paradigm-shifting?

There have been 10 million buzzwords to describe the future of work. I think the word “flexibility” distills the biggest shift in the conversation into one simple concept. Offering people flexibility gives companies a competitive advantage. Not just flexibility in how and where people work, but flexibility as a prevailing spirit that anchors the employee value proposition. This might also mean offering tailored accommodations for individuals’ unique family situations or capacities. And to me, this is really paradigm shifting because it breaks out of a prescriptive model of one-size-fits-all solutions.

During the pandemic, there was an explosion of more people thinking about what works for them. There was a glorious fleeting moment of workers having leverage. Even though there’s some pushback to that now, I think the culture has shifted to the point where prescriptive, one-size-fits-all solutions to modern work will not have long-term success. Different people require different things to do their best work. And work is already distributed and asynchronous by virtue of many large companies operating in several time zones and countries. We need to lean into that truth, that reality.

The companies that will attract and retain talent will be offering flexibility as the solution. Flexibility honors the individual, is less dehumanizing, and intersects with ongoing conversations about disability and DEI. A flexible culture treats people like adults. I think that's a big picture.

In a book interview you did with your colleague and co-author Doug Conant, you said something interesting: “Writing is leadership.” Can you explain what you meant?

So, at ConantLeadership, we talk about leadership as “the art and science of influencing people in a specific direction.” I had to find a way to connect to that personally because leadership, while it has become my area of expertise and one that I write about professionally, the art of leading people is not my calling. Then it occurred to me that writing is leadership too. It’s a tool of influence. When we write, we’re working to persuade. We’re working to delight. And we're working to tell a story about what it means to be alive. In creative writing, I can expand the idea of influence to explore a theme or an idea with the reader.

That makes sense. Being a leader isn’t my calling either, but of course I’m influencing others. Everyone is. So, it seems thinking of myself as a leader might help me be more thoughtful about the kind of influence I want to have.

Yeah, that's a really good point. Leadership isn’t hierarchical. Anybody can become a leader in some area of their lives. And that's a really empowering idea.

The divide between our work and personal lives has blurred in the past few years. How are you navigating this changing dynamic?

I love this question because I think about it a lot. There's a bit of a disconnect between what I believe and how I behave because, truly, I'm cheering this change on as a spectator. We should not be treating workers like emotionless automatons; they should be free to be open about the fullness and complexity of their humanity. But like most things, I'm navigating this change very slowly and cautiously in my personal application. So I'm still guarded about sharing certain things.

On my substack, I’ve been much more vulnerable than what has been comfortable for me in the past. But sometimes I do find myself holding back thinking, “What if x, y, or z person reads this and it changes their perception of me?” And there are certainly things I don't feel comfortable talking about yet. But I’m working on it and admire people who are even more forthcoming than I am. I love how open you are in your newsletter about your family and your upbringing.

My college was excellent at training me as a writer, reader, and thinker. But I left feeling very unequipped to transform those skills into a career.

It's always a personal choice and may not be right for everyone. Timing has a lot to do with it. You’ve shared a lot on your Substack too. I love reading your thought process on every topic you write about. After reading your essay “How do we mourn our own lives?” I was wondering: Do you feel like you’ve gained a broader perspective from waiting tables in your twenties rather than immediately entering a too-often bubbled, professional monoculture?

Definitely. I don’t mean for this to sound judgmental, but I do believe if you’ve never worked in the service industry in some capacity—not just as a summer job but actually relying on that work to pay your bills in adulthood—you're missing a very important perspective and experience.

I also think it helped me learn how to adapt. After I graduated college, I had no idea what to do. No connections, no concept whatsoever of how to pursue a writing career. My college was excellent at training me as a writer, reader, and thinker. And I truly cherished that education (even though I’m still paying off my undergraduate loans). But I left feeling very unequipped to transform those skills into a career.

So it was like, okay, I know how to wait tables because I’d worked at restaurants in college, and I need to pay rent, let’s go. And I was able to support myself throughout my twenties despite not being on a typical “career track.” Which is not to denigrate the service industry which can be an incredibly fulfilling career, especially if more restaurateurs offered a living wage, health benefits, and paid time off, as they should. But it was not what I wanted to be doing long-term.

While I’d like to say I have no regrets, I do wish I’d unlearned some limiting attitudes about work earlier. Although I grew up with solidly middle-class parents, they worried about money and it was a frequent topic of conflict and angst in our household. I went to public school in an affluent suburban school district so there was this disconnect of being surrounded by people with money but not understanding the social “rules” that accompanied those privileges And there was a feeling of striving unworthiness, and being an outsider, that partly comes from growing up with a proximity to wealth without being wealthy.

I can relate. My parents were the first in their families to become solidly middle class. So much focus is on getting there. But you can get there and still feel insecure. Because then there’s the fear of falling behind or not fitting in.

Yes, there was a household pall of stress and discord around money, employment, finances etc. and this perhaps instilled a kind of insecurity and subservience around work. The resounding message was that no matter what, I had to have a job, any job, and should feel lucky to have it. I didn’t feel like I had agency; jobs were not framed as things that you necessarily choose based on your preferences or lofty aspirations. They were things that you gratefully seized when offered and endured for as long as you could hold on to them. This has informed a lot of my employment behavior including why I stayed in my job as a server much longer than intended. And those values continue to affect my attitude in ways I’m only beginning to understand.

I wonder how you’ve learned to function so well in your role with ConantLeadership. It seems like interacting with people in high-status positions would be stressful. Even when people are nice, power differentials, by their nature, can be intimidating.

It was daunting at first. I remember earlier in my career, my boss Doug would be like, “Oh, call up the Chief Human Resources Officer of Campbell Soup and interview them.” I would have a lot of anxiety about that. But also pride to be trusted with the job.

And like any skill, it got easier the more I did it, even though it was initially intimidating. Learning the jargon really helped as did developing competence in both the subject matter and how to conduct interviews. Being prepared is important. I’ve learned a lot about leadership, organizational behavior, employee engagement, corporate strategy etc. over the years through my work in this space. I probably interviewed 30 people for the book, including former C-suite, Fortune 500 CEOs, and executives, and have moderated Q&As with many more high-profile people in webinars and town halls.

At the end of the day, I’ve learned that they’re just people too. Mostly, they want what any of us want—to be treated with respect and to be heard.

Gen Z is much more awake to the fact that company cultures that allow them to be happy and to be themselves can be measures of prestige too.

You summarized a BBC article in a ConantLeadership newsletter about Gen Z redefining what career “prestige” means. I definitely see this. Are younger people in your life inspiring your own career choices, including future hypothetical ones?

I love how Gen Z is shaking the table–at least in the workplace. They understand flexibility is important to living a full life. They're passionate about seeing their values reflected in their careers and workplaces. They’re challenging the striving mentality where you must endure uninspiring work, follow rigid rules, and prove your worth — just to survive. As discussed, it didn't occur to me to pursue things with agency when I was their age.

Gen Z is much more awake to the fact that company cultures that allow them to be happy and to be themselves can be measures of prestige too. And I'm so excited to see how Gen Z will transform the world of work. I hate articles and clickbait that try to pit the generations against one another. It drives me nuts. It's a tale as old as time.

For millennia, older generations have grumbled and railed against the younger generations. They turn them into this vessel for all their grievances. I'm an elder Millennial, and I remember not too long ago, people were saying Millennials were lazy and entitled. Now people say the same thing about Gen Z. I mean, come on.

And young people in my generation were called slackers.

Yeah, Gen X was the slacker generation. The complaints don't change: It’s always this accusation of laziness or entitlement, the same canard. Anecdotally, I saw that Pew Research decided to stop using generational labels altogether because they said their research shows that birth year is not even an accurate way to measure trends and behavior. They say that there are similarities through generations that are more significant.

Yeah, if you go into a high school, it’s not like the kids all think and act the same just because they were born around the same time. I also wanted to ask you about screen apnea. You mentioned it in a recent newsletter.

Absolutely. I read about screen apnea in a recent New York Times article. Screen apnea describes the detrimental physiological effects of having our nervous systems repeatedly activated by notifications, emails, and text messages. It’s like sleep apnea, except it refers to how our breathing is affected by prolonged exposure to screens.

The more out of the blue the notification, the more likely your body perceives it as a threat. Having your threat response switched on and off all day puts your nervous system into this depleted, exhausted state, causing shortness of breath. It’s damaging to our health.

I found this so validating because I find all notifications, but text messages in particular, to be stressful and irritating to an outsized degree. I have to mute threads. I sometimes feel like my phone is antagonizing me and I'll keep it in another room when I'm working or focusing. So when I read that article, I was like, oh, there's a name for that out there. I’m not the only one feeling this.

I hate letting people down. I’m trying to remember that it’s equally painful to let myself down—and that other people can manage my saying no.

You’ve said it’s easier to do something and get it done when someone else expects it by a deadline. With your novel, how are you managing your work on it?

It has been difficult. Because I’m writing this on spec. There is no project manager or editorial body demanding this work from me.

It has helped having the experience of ghostwriting a book (The Blueprint) with external deadlines. That taught me self-trust and showed me that I had the stamina and discipline to complete a long piece of work. But it’s different when it's just you. I saw a tweet that made me laugh that said something like: “Everyone thinks they want to write a book but trust me, you don't. You're just giving yourself adult homework for no reason.”

As somebody with ADHD, time management and productivity are always a struggle. I try to honor that my capacity is different than some people’s. I've had so much shame throughout my life, feeling like I should be able to do more. I’ve found that when I lean into acceptance about my capacity rather than fight against it, I can get more done. I have to block off time on my calendar for down time and for writing and then be disciplined when things inevitably conspire to encroach on that time.

Part of it is learning to say no to things, which is always a struggle. I hate letting people down. But I also hate saying yes to things that I don’t want or am unable to do, which has been my modus operandi for a long time. Now, I’m trying to remember that it’s equally painful to repeatedly let myself down—and that other people are adults who can manage the disappointment that might come from my saying no. Easier said than done, but I’m working on it.

Me too. I love how you framed that. I heard you talk about a need to “engineer accountability” when there’s none built in. It sounds like self-compassion and managing boundaries are helping you find time and focus for your writing. Is there anything else that’s working for you?

I also tried to engineer some external accountability by telling everybody I was writing a book. I've been working on this since late 2020. It is now late 2023. I have 80,000 words in my rough draft. I thought I’d be long finished revising and querying by now. But it still needs wholesale revision; it needs a lot of meticulous editing. Quality takes time and I am fastidious. I wish I had some magic tips. But when self-loathing creeps in, when I regard a vast landscape filled with people who are writing more, better, faster than me, and feel a crush of doubt, I try to take a step back and appreciate that I have come this far. Sometimes, I can't believe I’ve actually written that much of it while also working full-time for the most part.

Sometimes, just getting through something is what teaches the most.

Yeah, my reflex is to judge and shame myself for not doing more. But I'm trying to reframe that and think, well I wrote a draft of a novel on spec that nobody's paying me to do, propelled only by my own desire and will. And there have been busy months where I’ve barely been able to work on it at all and I always come back to it. I'm trying to remember and feel good about that, to be proud of myself for daring to pursue my dream. But still, it's hard. I suspect that all writers, maybe even all creatives across mediums, struggle with this.

Beautifully said. And I agree, process doesn’t get the respect it deserves. But reframing can help give it value. Thanks so much Amy, truly. It’s been a joy getting to know you better.

South Philly Author, Editor and Ghostwriter Reveals Why She's Ready To Be Unmasked

Amy Federman’s Celebration newsletter is a doorway into her headspace. It’s a fascinating place where you’ll hear Amy’s thoughtful takes, full of nuance and fun. Topics range from sharing the messy middle to artificial intelligence to becoming a creative risk taker