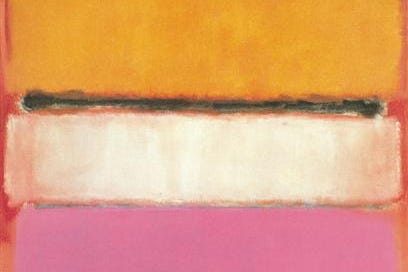

“A painting is not a picture of an experience. It is the experience.” - Rothko

In early 2020, shocking news traveled across the internet: There are people who don’t have an inner monologue. They have thoughts, but they are not transmitted via stream of consciousness or a “voice.” These miraculous humans live a peaceful life (or so I imagine), free from the tyranny of words rattling around in their heads.

This piece of trivia went viral, spawning a flurry of memes and press coverage. The shock of the discovery was mutual between those who hear an internal voice, and those who do not; neither party had considered that the other existed.

As someone whose brain never shuts the hell up, I was unmoored by the news. It seemed unfair that some souls are spared the noisy interior I’ve got clanging around.

Daily, my mental habitat is abuzz with an unyielding flow of language from the moment I blink awake. More or less, it’s in my own voice, and often in sentence form; I’m talking to myself near-constantly, whether I want to be or not.

Sometimes my inner voice is helpful or beautiful or surprising, other times it’s sarcastic or arch, and often it’s interesting—but it is also intrusive, exhausting, and banal in equal measure. OCD inflames my neurons with upsetting thoughts and ruminations. ADHD causes self-flagellation, confusion, and delays. And as much as the voice in my head can wax poetic, say, while luxuriating in a sunset, or reveling in a salted ocean breeze as it whips through my hair—it’s also an insufferable nag, reminding me constantly of the administrative drudgery that staying alive requires, hurling an onslaught of reminders about tasks, errands, duties, and obligations.

And worse: it’s too energetic. Even when I’m dead tired and just want to sleep or relax, the voice in my head flits about, trying to draw connections, to make sense of my experience, to spin a narrative around my life. Like a plucky beat journalist sniffing around a crime scene, my inner monologist always wants to know, “what’s the story here?”

And sometimes the story is I just want to lie on the couch, or eat scrambled eggs, or feel a feeling, or fall asleep—and not have to be actively processing every sensory input via verbose thought-thread. Please.

So, learning that some lucky specimens are born into a quieter vessel was upsetting. Or maybe aspirational. I found myself wishing my nascent embryo had been informed of the more serene option. It’s hard not to be envious of people like the man in the following excerpt from this piece in The Guardian:

Hopkins, who is 59 and works for a social enterprise in London, doesn’t have an inner voice. There is no one in his brain to blame, shame or criticize. In his head, there is emptiness: just the still warm air before a rustling breeze.

“There’s nothing there,” says Hopkins. “And I don’t think there ever has been.” Of course, Hopkins has thoughts: we all do. But the inner monologue that fills our brain while the engine stands idling isn’t there. It’s been clicked off, permanently. “When I am alone and relaxed, there are no words at all,” he says. “There’s great pleasure in that.” He can easily while away an hour without having a single thought. Unsurprisingly, Hopkins sleeps like a baby.

Must be nice. But, alas, we can’t all be like the blissful Hopkinses of the world. If you’re like me—noisy inside—hopefully you’ve managed to find some liberatory ways to quell the voice, or at least give it some temporary fodder to help it settle down.

I like to think of some of my most beloved coping mechanisms as ways to get past the security staff in my consciousness, to pull off a heist: I throw the hungry guard dog of my mind a treat, something to satiate it and stop its gnarling so I can slip past the iron gate, into a quieter place, a plane of feeling more than thinking, a realm beyond words. Doing this, I know the guard dog won’t be satisfied forever, but at least for a time, it can rest and I can play. This is how I access a more expansive sensation of being alive—a glimmer of what my counterparts with no internal monologue might feel.

Some of the most powerful treats for my guard dog are abstract art and jazz music. As much as I love escaping into a book, or numbing out to crap TV, or exercising to get out of my mind and into my body, I’m often most calmed and nourished by art forms that transcend language—media that has much to express but doesn’t rely on words as the messenger.

—

As a young BFA student in writing and literature, some of my favorite classes were not about writing or literature at all (although I loved those too); they were about the visual arts—learning how art was, to use one now-cringe expression, in “conversation” with other art, across mediums.

In college, something crucial coalesced: a zoomed-out view showing how the world interconnected. I began to understand that everything existed in relationship with everything else. The paintings, and buildings, and novels, and fashions of a time-period were a snapshot, reflecting the state of humanity. Each era had its own oeuvre, a kaleidoscope glimpse into the collective consciousness that was always changing, and could be looked at a thousand ways, each time revealing something new. And all the works had shared artistic ancestry—a line traced to what had come before and would show up in the works afterwards, for generations.

There was millennia of context behind everything. Nothing just was; it was all linked.

My teenaged brain gobbled up this new, cavernous understanding of the world. There was a vague sense of vindication: my long-standing but hard-to-articulate suspicion that there was more to things than meets the eye was finally validated. It felt like exoneration: “See! I don’t ‘overthink’ things and ‘read too much into them’,” as I’d often been told. No, it was right to look deeper after all; everything really was abloom, teeming with history, and ripe for analysis (just as my inner voice had suspected). It was all dripping with meaning, down to the arches on the doorways, the slang that we used, and the shoes on our feet.

And then, just when my synapses were awakening from what had seemed like 12 years of slumber in public school, I got another jolt to the system. Mark Rothko.

In a sophomore lit course ostensibly about American Minimalism—one blessed professor introduced us to Rothko, a Latvian-American artist who died by suicide in 1970. Now, he’s a household name, but he wasn’t yet on my radar as a 19 year old in 2002.

Our professor explained that Rothko aimed to create a purely emotional experience with his paintings: displays that were beautiful but rebelled against the compulsion to project a story onto everything. He didn’t want his paintings cheapened by the vulgarity of analysis. Astute and prescient, Rothko saw a bleak futility in our instinct to narrativize. He found it limiting to default to a single mode for processing our environment; some things in life must be metabolized differently.

Learning about Rothko’s rejection of narrative was one of my first inklings that there were ways to get the voice in my head to shut up—at least temporarily. And that doing so was not mere novelty; it was important. Here was a way to process being, a fuller realization of being alive.

I needed to know more. (And I was lucky to have a great teacher; his love for Rothko poured into his lessons.)

Rothko’s half-cranky, half-jubilant message was: My paintings aren’t about anything. They are not stories about you or me; they are experiences for you, for me, for all of us. You don’t have to do anything to understand them; they are defiant. They do not want to be processed cerebrally, they want to be processed somatically, in your body, in your nervous system.

There was an ease to his mission: Don’t strain. Don’t squint to glean the meaning.

Let go.

And it made sense. Rothko’s best-known works were painted in the wake of World War II, one among many atrocities that have ravaged humanity. The despair was unspeakable. Of course words were insufficient, the intellect not up to the task. What could there possibly be left to say about so much death? What’s left to think?

The bold blocks of color in his paintings were an invitation: Stop trying so hard. Just feel it. Relax, give the dog in your mind a treat, and succumb to emotion. This is why many people famously cry when they see a Rothko; his message is received, transmitted without words, from a state of surrender.

It’s easy to see why I loved Rothko instantly. My inner voice and I, newly excited by curricula that enabled our chattiest impulses, stood at attention. Paused. Analysis, drawing connections, yes—it mattered. But there was something else, beyond reason, beyond wits: art that wasn’t meant to be inspected, wasn’t intended to be beaten with the cudgel of comprehension until its “true” meaning bled out from the cracks.

Less really could be more (she wrote in a two-thousand-plus-word essay). Or, the secret to accessing the more was found in embodying the less. Less thought, more awareness—leads to knowing of a different kind.

I was delighted. Artwork without a story to tell offered permission to step outside the stifling container of narrative. It was a revelatory reframe, especially within the context of a creative writing curriculum. What a gift—that there were marvels to experience beyond the orthodoxy of language.

“I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions — tragedy, ecstasy, doom, and so on — and the fact that lots of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures shows that I communicate those basic human emotions . . . The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them.” - Mark Rothko in a cranky exchange with Selden Rodman

When I finally stood before the Rothkos at the MOMA in New York a few years after college, I was relieved when I wept. I’d been worried. Their promise had been so enticing, their lesson so treasured—such a beacon of hope for my clamorous brain—that part of me feared I’d be immune, cursed with a mind too noisy to let myself go. But, no. If anything, they exceeded expectations. I cried for several minutes.

Humbled by the scale of the giant canvases, many of them over 9-feet tall, I trust-fell into the brilliant paint-swaths layered atop one another in meditative blocks, stacked cairns of color, trail markers for the mind, letting me know, “you’re on the path, right this way, it’s safe to wander. Don’t intellectualize the picture, feel the painting.” Their grand size was apt—matched to the vastness of the human experience—larger than a full-length mirror, reflecting our infinite capacity to emote, to perceive.

Now at 40, I’m lucky to have witnessed Rothko’s works many times. And while they don’t always leave me weeping, they always quiet the voice in my head. They’re doorways to another sphere, reminders of a voluminous consciousness—the limitless expanse of sensory awareness available beyond words.

_

Last month, I went with some dear friends to see a jazz quartet led by a gifted young trombonist, Kalia Vandever. One of their ballads was so delicious to my mental guard dog, I was transported to the feeling plane before my conscious mind even noticed: The mournful vibrato of the trombone swelled into triumphant phrasing and then retreated into breathy release. There were soft waves, ups and downs, lulling decrescendos. Ebbs and flows. It moved me. My inner voice fell quiet as my eyes welled up. So much was expressed—poetry without the poem.

After the ballad, Kalia explained that the song was about the last words her grandfather had said to her before he died. Yes, I thought, that clicks. It jived with the sweetness and solemnity of the music. And the explanation was lovely. But it was also redundant to the song itself. Instinctively, our nervous systems already knew what had been expressed. The music had told us something sad and beautiful, which is the only thing there is to tell about being human. The essence.

To be alive is beautiful—joyful, funny, ecstatic, careening, wild, mysterious, and enchanting. And it is sad—marred by grief, loss, injustice, rage, despair, and anguish. It is both, always.

Maybe music, art, language—it’s all a buoyant, miraculous, fumbling attempt to express that paradox: the simplicity of it, and the impossible, fathomless complexity of it.

Rothko knew that the immensity of the both-ness—the brutality and the beauty—can’t always be said, sometimes it must be felt. And we have to get out of our own way to roll around in that essence. To reject the narrative, to transcend story.

Songs and paintings are my conduits to the essence, but they don’t have to be yours. Many people can’t see, or hear, or speak and they are just as capacious in their feeling and sensing of the shared, enormous mystery of being human.

I’ve always known (probably we all know): There’s more to things than meets the eye. Millennia of context in everything. In our cells, bodies, genes. Sad, beautiful, interconnected. It is so much to hold. And language isn’t enough; it breaks under the weight.

More and more, I cherish the wisdom Rothko awakened in me years ago—that the intellect is not the lone or best path to deeper understanding. Inner voice or not, there is a sensory place within the human being that is only accessed beyond the veil of words; my guard dog and I remain in hungry pursuit of its quiet rapture.

PIECES OF MIND

Reality is construction work with countless duties, difficultties, formats and goals. In this way, it is a full-time job with guaranteed lifetime longevity—conditional, of course, on performance skill and health to maintain it. “To live is to defend a form,” wrote the 19th century German poet Friederich Holderlin.

Reality is, in this way, an art form practiced in many mediums—some involving words, others involving clay, pigment, stone and wood. Holderlin often found refuge from internal commotion and stress in the sight of mountains, meadows and streams. Seeing them, he wrote, he felt cradled in the arms of the gods. I see this as exercising sublime craftsmanship. You are ebing "craftera' as much as what is being crafted.

But looking inside can also produce the same beauty and beatitudes as looking outside. Often this art is perfection of yogic awareness whose end-product is simply calm understanding or any instance of insight. Their end result may be purely behavioral and cognitive. Nothing physical is created. But there is a transformative realization that alters behavior. Whatever, everything you see, perceive or feel involves construction—from instant snapshot, profound glimpse, lasting insight to projects involving unassailable concentration, formidible struggle and hard testing.

An exclusive component of human being is acceptance of and commitment to reality construction. This membership in the reality construction trade is a species trait and human family heritage. You must practice reality construction and maintenance as if it were a family craft for which you trained and are continuance

In short, mind is like an employment agency for all media of conscious. That’s why inner voices and directives have many channels of expression—some “verbal,” some non-verbal but all summons to reactive attention and perception. Some summons are simple but give deepened awareness of the moment at hand or sustained troubling circumstances or chaotic surroundings. Practiced perception commandeers focus of consciousness in ways both tangential and non-tangential to ongoing circumstance. Even if one falls silent or distant, this is not work stoppage. You are organizing the moment for optimal participation in it.

Meditation and concentration often instigate seemingly self-sourced experiences not directly referential to any ongoing action or event. There is what a French philosopher Gaston Bachelard calls a “sudden salience on the brain,” like an eruption of solar fire on the sun. These seemingly discontinuous moments sometimes seem to bring disrupton but then give way to insight and vision. These saliences produce or cognize a new kind of coherence beyond any known before. The manner of understanding is as unforgettable is its matter. You know you will never think or feel the same way again about obsessive content or habits of behaviir. You feel shaken out of customary thinking and habitual reposne. Yes, recurrence of despair is always a possibility. But you learn methds of dissipation.

When painter Mark Rothko claims his paintings are self-contained experiences, he means that his art is non-narrative and non-representational except of and in itself. The idea that art can be its own origin was not new to him, but represented a culmination of history. Poet Philip Whalen famously defined a poem as “graph of mind moving.” Both poet and painter were saying that art was an event or occurrence of its own self, with no reference beyond its manifestation and no need to be “about” anything other than itself. The same can be said of cave paintings that are as much about action and movement as physical depiction of animals and objects. Thus they invoke benevolent feelings instinctively associated with their “subjects.”

Whatever the nature of the event inducing or inspiring response, they all take place within a profoundly inclusive, often all-encompassing realm, called consciousness. As aspiring poet, I am used to a verbal component to events. But there are times when the words were more like ornaments or afterthought and not integral to the experience they “referred” to or were born of.

Since my wife turned our back yard into a bird sanctuary, we have learned that each species that visits us has its own distinctive sound with what could be thought of as vocables. We love waking up to bird commotion every early morning. We know now the birds aren’t jabbering. They are conversing.

And so all living things are engaged to differing degrees in reality construction. Whether bird chirp or Sistine Chapel, all utterances are pieces of universal mind. The world becomes more intelligible. Those who know how to read the moment are practicing luminous literacy.

IMPLICATIONS

for Amy

1

Just as the Creation is a work-in-progess,

you are architecture under constant construction,

building site and sight of it.

Let every moment on site

lead to insight

that is resurrection of purposeful being.

2

Let the mountain in the distance

or the dried musroom ready for consumption

imply your equality

once seen or eaten.

This completion

is your latest success

at wholeness.

3

Let recurrence of bare birch

imply the emptiness

that is your origin

and final resting place.

Cross state lines

from confusion to contentment.

4

The thirst for meaning is endless

as is the brigade of phenomena

that brings water to quench it.

Crazy as it sounds,

the cliffs are starving

for their meetings with eyes

questing for the sight of beauty.

--David Fred Federman, 7/19-20/24

This essay was so beautiful, Amy! I realized that we share more than birthdays. I, too, have an internal voice that won’t shut up - and yes, it does sometimes drive me crazy! Diverting books, read and listened to, and movies, too, are ways to shut it off briefly, but you taught me why art is such a comfort, too (and your Dad and I well know the joys of music as distraction!).

I, too, had an encounter with Rothko when I was young - I was living in London on a theater fellowship and I used my days between shows to walk London and visit museums. One day at the original Tate Museum, I stumbled into its Rothko room and found a kind of peace I had rarely known. I also finally understood what it was to feel without words, just as you said. It was an epiphany for me in understanding abstract art - I didn’t need to verbalize it - the feelings were enough. I’ve never forgotten it. Glad to know we are kindred spirits in more ways than one.